This week I speak with Meat, the main character in This Lawless Land, a six book post-apocalyptic series. The first book, All Roads Lead to Terror will be updated next week.

1. Can you describe what motivates you to keep going in such a harsh, post-apocalyptic world?

I guess what keeps me moving is the hope that things can get better, even if it’s just for a little while. I’ve seen too much loss to believe in miracles, but I can’t just sit back and let the world swallow up the people I care about. Maybe it’s stubbornness, or maybe it’s just wanting to prove I’m more than what my name says I am. I want to help others survive, especially the kids who got taken. If we don’t look out for each other, who will?

2. How did your upbringing shape the person you are now?

My childhood was a mess—always running, never safe, never really wanted. My mom called me Meat because, to her, that’s all I was. I grew up with survivors, not family, and learned early that you can’t count on anyone but yourself. But I also learned that sometimes, you must step up for others, even if it hurts. That’s what makes you more than just Meat to the world.

3. What does leadership mean to you, especially when you’re leading other kids?

Leadership isn’t about being the loudest or the strongest. It’s about making hard choices and carrying the weight when things go wrong. I never asked to be in charge, but people look to me because I’ve survived outside the fence. I try to keep everyone together, even when I’m scared or unsure. Sometimes, all you can do is keep moving forward and hope your choices don’t get someone killed.

4. How do you handle fear, both your own and that of your friends?

Fear never really goes away. I feel it every day, especially when I think about what could happen to the people I care about. I try not to show it, because if I fall apart, so does everyone else. I focus on what needs to be done. Tracking, fighting, surviving. If I let fear take over, we’re all dead. So, I push it down and keep going.

5. What do you think about the rules at Bremo Bluff, especially the ones about outsiders and survivors?

The rules at the Bluffs are harsh, but I get why they exist. If word got out about what we have—electricity, water, safety. Everyone would want in, and we’d be overrun. Still, it doesn’t sit right with me that people who know about us can’t ever leave. It’s like a prison, even if it’s for our own good. Sometimes I wonder if we’re really any better than the people we’re afraid of.

6. How do you deal with loss, especially after everything you’ve seen and done?

Loss is just part of life now. I’ve lost friends, family, even people I barely knew. It hurts every time, but you can’t let it break you. I try to remember the good things, the small moments of hope or laughter. But I also use that pain to keep me sharp. If I forget what I’ve lost, I might get careless, and that’s when people die.

7. What do you think about hope? Is it a weakness or a strength?

Hope is the only thing that keeps us going. Without it, we’d just give up and let the world win. It’s not weakness to hope for something better, even if it’s just a hot meal or a safe place to sleep. Hope is what makes us human. It’s what separates us from the monsters, both the dead and the living.

8. How do you view the adults who survived the awakening compared to your own generation?

Most of the adults are broken by what happened. They remember the world before, and that makes it harder for them to adapt. My generation, we never really knew anything else. We grew up in the ruins, learned to fight and survive from the start. Maybe that makes us harder, or maybe just more desperate. Either way, we’re the future, for better or worse.

9. What’s the hardest decision you’ve had to make so far?

Letting go of the idea that we could save everyone. Sometimes, you must make choices that haunt you. Like leaving someone behind or doing what needs to be done to protect the group. The hardest was probably agreeing to the council’s rule that there could be no survivors among the kidnappers. It made me question if we were still the good guys.

10. If you could change one thing about your world, what would it be?

I’d bring back a sense of safety, even if just for a day. A world where kids could play without looking over their shoulders, where families didn’t have to choose between survival and their humanity. I’d want a world where names mean something, where you’re more than just a walking bag of meat to the people around you.

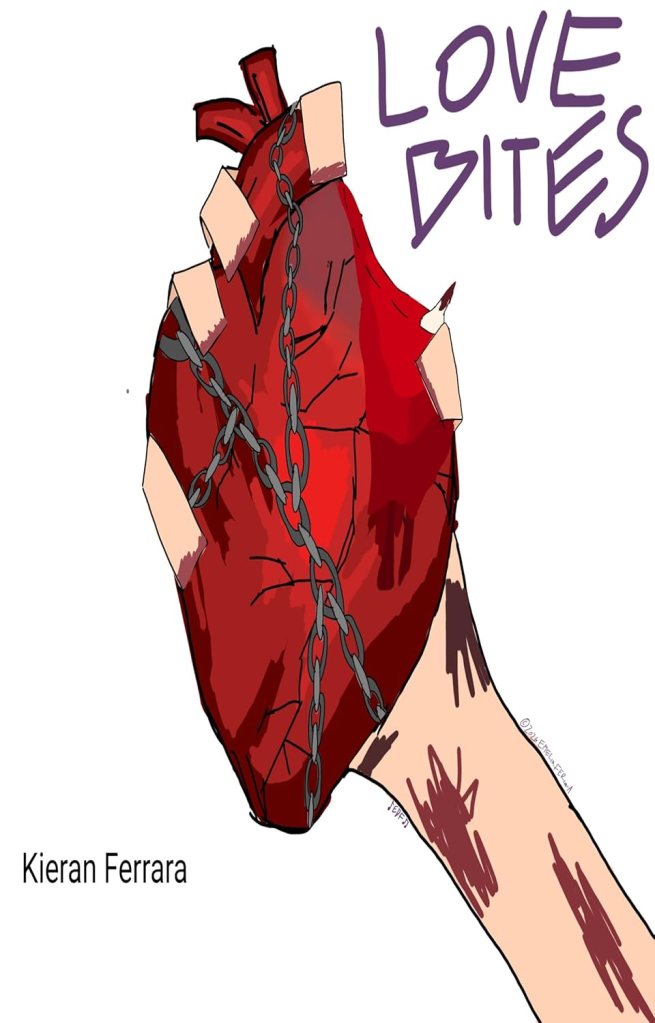

In the coming months you will have the opportunity to follow Meat’s story as the series is released in its entirety. I’m nearly done with the final book and have hired a good cover designer to help me bring these stories to life.